Linux kernel module : Building a soft UART for the Raspberry Pi - part1

The RPi is a well-known platform intended for educational use. For its compact form and relatively low cost, this board has become very popular among enthusiasts and makers. The RPi is used in many projects from different fields, eg. Robotics, IoT… where it’s linked with different types of sensors and detectors.

In many cases, the sensors that are used, adopts a communication protocol such as SPI, UART, I2C for wired communication, or wireless using protocols such as Bluetooth and ZigBee. The most adopted, and easy to use of serial protocols is the Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter (UART for short).

Unfortunately, all versions of the RPi until version 3, comes with only two UART ports : A full featured UART (PL011) enabled by default (GPIO’s 14 and 15), and a mini UART with a reduced feature set (used by the wireless LAN/Bluetooth controller, on models which contain this controller) that necessitate some tweaking to get it working at first (modification of the Device Tree Overlay basically). This hardware limitation of the RPi can be a complication for projects that needs more than the two UART ports, especially for RPi models that doesn’t have much of peripherals (eg. RPi Zero).

The idea behind this project, comes to tackle this specific problem by creating a software UART compatible with all Linux based boards including the RPi. Because it’s a software implementation, it has only the minimal features required to establish a reliable serial connection. As you will find throughout this 2-parts write up, the software implementation obviously can’t compete with the real hardware port, nevertheless, it offers a decent alternative.

You’ll find all the written code in my Github.

Linux driver

Yes, I opted to implement this software UART port inside the Linux kernel as a Linux driver (a.k.a Linux module). If you are not familiar with Linux modules, they simply consist of a chunk of code that runs inside the kernel space, basically to add useful features to the OS or support to some device or user app, and it can be loaded/unloaded into the Linux kernel at runtime. The advantage of Linux modules over the applications that runs in the user space, is that they have higher execution privilege and generally run’s faster than the user space apps. As we are trying to emulate a hardware protocol by software, speed of execution is a real concern for us, hence, the implementation as a Linux driver.

UART serial port

Before starting the implementation of our driver, we need first to take a look at the inner working of the UART protocol.

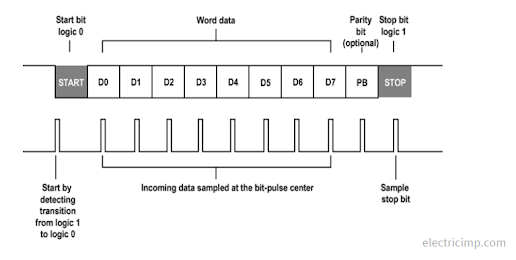

Below is a general summary of how the UART protocol works.

The UART protocol is a two-wire protocol: transmit Tx and receive Rx, that lets two nodes exchange data asynchronously. To synchronize data sampling, the transmitter adds to each data word a start and a stop bit (the stop can be 1, 1.5 or 2 bits long), along with an optional parity bit that helps protecting the integrity of the data word.

Each packet contains a data word that can be 5 to 9 bits long. When the receiver detects the start bit in the Rx line, it starts sampling the data at the frequency specified by the baudrate (bits/sec). Additionally, advanced UART’s implements a hardware flow control (HFC) which is basically a strategy for communication between slow and fast devices without data loses.

UART is a very simple protocol, however, its software emulation rises some exclamation marks about software preemption and the execution speed. As a matter of fact, like all other programs that runs on the processor, our Linux driver will obey to the scheduling policy of the Linux OS and depending on the baudrate used, the UART protocol can impose very strict timing constraints: Each bit that is transmitted via the Tx line, takes 1/baudrate seconds to be sent. Therefore, if we consider that the receiver samples the data bits exactly at the middle, 1/(2*baudrate) will correspond to the maximum allowed difference between the sender’s and the receiver’s baudrates, e.g. for a baudrate of 9600, the max allowed difference between the two baudrates is ~52 μs.

As a consequence, to avoid preemption and speed problems, in our implementation we will try to minimize all critical parts in the code and we will consider only the following minimal feature set of the protocol:

- Data word size of 8bits.

- 1 start and 1 stop bit.

- No parity bit.

- No flow control.

What is a Linux TTY driver?

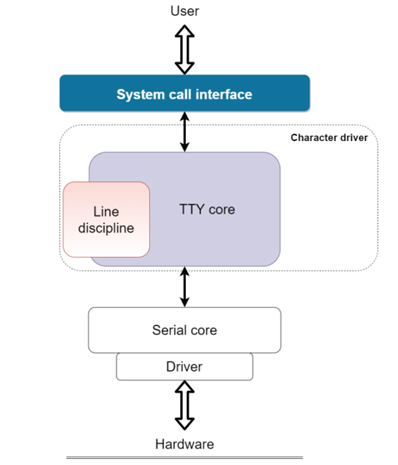

The name of tty devices came from the old abbreviation Teletype (writer), and it is commonly associated with serial devices. For a serial port to be properly integrated under the Linux kernel, it must be visible as a tty device from the user space, and for that, any serial driver must be implemented in the tty kernel subsystem.

The figure below, shows the implementation of the tty subsystem under the Linux kernel:

The tty core driver is implemented as a character driver under the Linux kernel, and it offers a set of functionalities that serves as an interface for serial devices. This driver is responsible of controlling both the data flow and the format of packets passing through it, allowing serial drivers to focus on the low-level hardware interactions instead of worrying about data exchanges with the user space. In addition, tty core include a set of extensions called ‘lines of discipline’ that mounts between the tty core and the serial driver enabling extended functionalities to the serial driver (by default, tty core uses ldscp N_TTY which directly link the serial driver to the user space).

Until version 2.6 of the Linux kernel, serial drivers were implemented directly under the tty core driver inheriting a non-negligible complexity for the driver development. However, since version 2.6, a new interface, serial core, was implemented under the tty core to ease the development of serial drivers.

In this project we will implement our driver under the serial core interface, but before that, one of course must have a functional and structural understanding of the APIs offered by this interface and how interactions with the low-level operations Tx & Rx are implemented. For that, one needs to analyze the source code of the interface: /linux/serial_core.h .

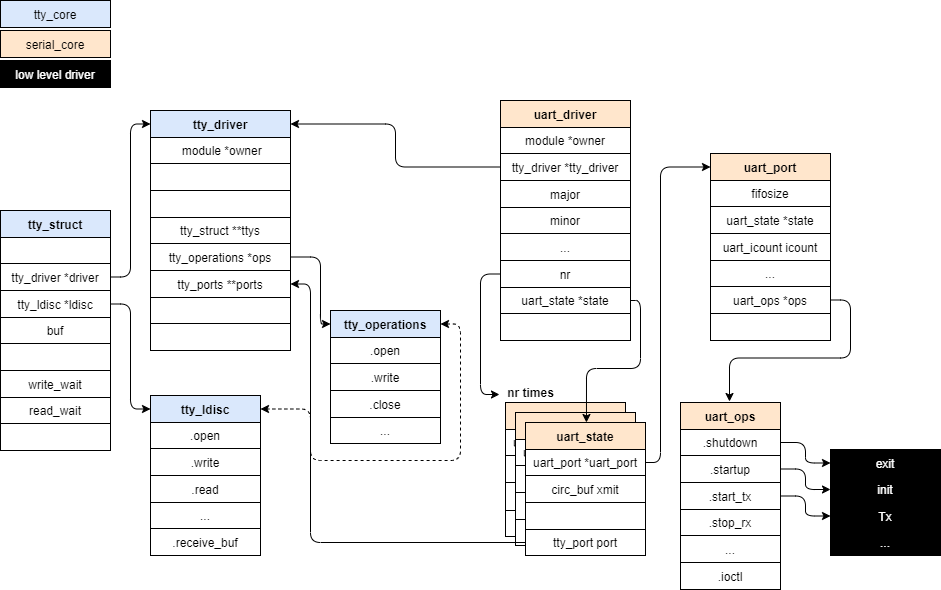

After thorough analysis, in the diagram below I show the important structural links of serial core with the top layer tty core and the low-level layer:

In fact, the use of serial core interface needs the definition of three main structures:

-

The structure representing the driver:

struct uart_driver -

The structure representing the port included in the driver:

struct uart_port -

The structure containing the pointers to the port operations:

struct uart_ops

Other structures are automatically initialized when the driver is registered on the kernel, and they must not be defined by the user e.g. tty_driver

Implementation

For organization purposes, (As we – informaticians – like to split things into layers) the implementation of the driver will be separated in two halves:

- A bottom half that contains the

UARTprotocol implementation and manages the low levelGPIOinteractions. - A top half which implements the actual

ttydriver and manages the interaction with the user space.

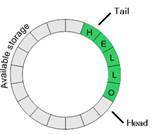

Before creating the code for the two layers, we first need to have some sort of FIFO memory to store received and to-send data. For this purpose, we decided to implement a circular buffer that will manage data exchanges between the two layers of the driver. Also, this type of buffer allows an efficient use of the fixed buffer size.

A circular buffer is characterized by two pointers that manages the read/write operations: a head pointer, always pointing to the top of the buffer (address of the next write), and a tail pointer that always points to the last element of the buffer (address of the next read).

In circular_buffer.h we will create the structure of our circular buffer which include the two pointers head & tail, a fixed size data buffer (of type char) plus a flag to indicate the status of our buffer:

struct buffer

{

int head;

int tail;

bool isfull;

unsigned char data[BUFFER_MAX_SIZE];

};

There will be two instantiations of this buffer: rx_buffer and tx_buffer so that data exchanges can be managed separately between the two halves of the driver.

In addition, we will define some basic functions that eases buffer manipulations:

- The

initfunction that resets the buffer pointers to zero:void initialize_buffer(struct buffer* buffer); - Functions to read and write one char into the buffer:

int push_character(struct buffer* buffer, unsigned char character); int pull_character(struct buffer* buffer, unsigned char* character);after each write (read) the

head(tail) pointer is incremented. This modification of the two pointers is implemented carefully following the circular buffer algorithm. - Functions to get the status of the buffer:

bool isBufferFull(struct buffer* buffer); bool isBufferEmpty(struct buffer* buffer);

Bottom half

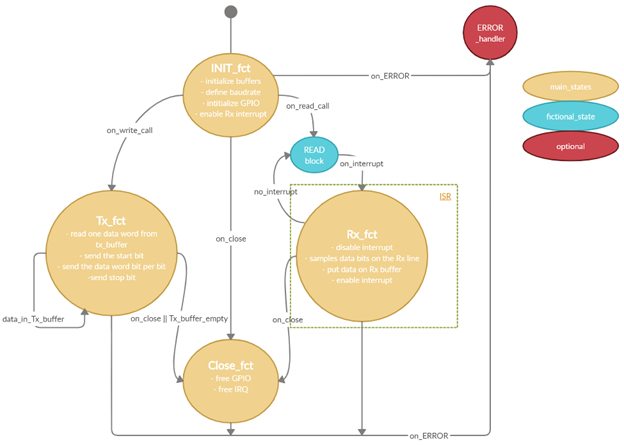

Now, let’s start our implementation of the low-level UART protocol. To make things more fun, I drew the state diagram below to sum up our implementation. As it’s only a half-duplex protocol, our code will have only one function to execute at a time: write or read.

In a new file soft_uart.c we start the definition of our main functions:

INIT_fct:

The first function is the init function, in which we start by initializing the Rx and Tx buffers, the GPIO pins (note : the idle state of the Tx pin is high), and we reserve the Rx line interrupt to be able to start receiving data (in the ISR) asap. We initialize also a reception tasklet that is used to pass Rx data over to the top layer (this will be discussed further below).

This function takes in parameters the GPIO pin number of both Tx and Rx (in our implementation we used pins 17 and 27 respectively), in addition, it takes a pointer to the serial port structure struct uart_port which is handed over to the receiving tasklet.

For the baudrate, we will set it as a global variable so it can be accessed by all functions of the driver.

int uart_init(const int tx, const int rx, struct uart_port *port)

{

int ret;

/*Initilize buffers*/

initialize_buffer(&tx_buffer);

initialize_buffer(&rx_buffer);

/*Initialize the GPIO pins.*/

gpio_tx = tx;

gpio_rx = rx;

ret = gpio_request(gpio_tx, "uart_tx");

if(ret<0) {printk(KERN_WARNING "gpio not reserved : %d\n", ret); return ret;}

ret = gpio_direction_output(gpio_tx, 1);

if(ret<0) {printk(KERN_WARNING "gpio direction not set : %d\n", ret); return ret;}

ret = gpio_request(gpio_rx, "uart_tx");

if(ret<0) {printk(KERN_WARNING "gpio not reserved : %d\n", ret); return ret;}

ret = gpio_direction_input(gpio_rx);

if(ret<0) {printk(KERN_WARNING "gpio direction not set : %d\n", ret); return ret;}

/*Initialize interrupt: rx trigger*/

ret = request_irq(gpio_to_irq(gpio_rx), (irq_handler_t) handle_rx_start, IRQF_TRIGGE

R_FALLING, "Rx_handler", NULL);

if(ret<0) {printk(KERN_WARNING "irq request error : %d\n", ret);return ret;}

else printk(KERN_INFO "irq requested succesfully ! \n");

/*rx_tasklet init*/

tasklet_init(&rx_tasklet, rx_tasklet_function, (unsigned long) port);

return 0;

}

Tx_fct:

The transmit function is implemented as a simple while loop in which we retrieve data – word by word – from the Tx_buffer and send it bit per bit, along with a start bit at the beginning and a stop bit at the end of each data word.

To respect the baudrate, we will implement a delay after each bit that is sent using the ndelay() function (nano-second delay). In addition, at the end of transmission, we call the uart_write_wakeup() function to wake up the upper layers and trigger the next transmission.

int uart_handle_tx(struct uart_port *port)

{

/*send wakeup to tty layer to begin next write*/

uart_write_wakeup(port);

/*send data*/

while(pull_character(&tx_buffer, &send_char) == 0)

{

//startbit

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 0);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

//data bits

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 0));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 1));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 2));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 3));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 4));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 5));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 6));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1 & (send_char >> 7));

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

//stop bit

gpio_set_value(gpio_tx, 1);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

//statistics : increment port tx count

port->icount.tx++;

}

return 0;

}

We’ve used the ndelay() function instead of htimer (which is a high resolution timer used in time precision based events) because the costs of frequently enabling and disabling htimers, in our use case, was experimentally judged of more harm than good (compared to using the *delay() function family) especially for high baudrate values.

Rx_fct:

The implementation of the receive function is divided in two parts: the first part, which is the critical one, directly implemented in the ISR of the Rx line and handles the sampling of the received bits, and a second part, implemented in a tasklet, responsible of passing the received data over to the top layer.

During the critical sampling part, for the interrupt to not be triggered by the data bits and scheduled by the system (the IT must only be triggered by the start bit), we must momentarily disable it using the disable_irq_nosync() function. The interrupt is reenabled after the reception of one data word. At the end, each data word is stored in the Rx_buffer and the Rx_tasklet is called.

Once again, we add nano delays between bits reception clocking out the sampling frequency. However, this time, we add a ¼ baudrate time before the first sample to avoid sampling at the edge (not ½ - sampling at the halfway point – to increase our jitter acceptance margin), also the reception of the start and stop bits is ignored using a dummy delay.

irqreturn_t uart_handle_rx(int irq, void *dev)

{

disable_irq_nosync(irq); /*disable the interrupt, so it's not triggered by the data bits*/

//start bit

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns + sleep_interval_ns/4); /*adding 1/4 offset time to avoid sampling at the edge. Not 1/2 (sampling at the halfwaypoint), so we can increase our jitter acceptance margin, as we are more likely to sample slower not faster than the baudrate.*/

//data

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 0);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 1);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 2);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 3);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 4);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 5);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 6);

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

receive_char |= (gpio_get_value(gpio_rx) << 7);

//stop bit

ndelay(sleep_interval_ns);

/*reenable the interrupt*/

enable_irq(irq);

/*push_character to rx_buffer*/

push_character(&rx_buffer, receive_char);

/*schedule tasklet*/

tasklet_schedule(&rx_tasklet);

/*reinitialize receive char*/

receive_char = '\0';

return IRQ_HANDLED;

}

In contrary to what their name implies, tasklets are not small tasks/threads, they are simply a mechanism that allows ISRs to execute a non-critical portion of the code outside its context. The tasklet is executed asap after the ISR is ended. Yet, only one call to the tasklet can be scheduled, if the tasklet is called a second time, only one instance is executed. In our case we implemented a while loop inside the Rx_tsaklet function in which we read data continually from the rx_buffer and send it up to the top layer.

void rx_tasklet_function(unsigned long data)

{

struct uart_port *port = (struct uart_port *) data;

unsigned char c;

while(pull_character(&rx_buffer, &c) == 0)

{

/*insert char inside the serial_core with the appropriate flag*/

uart_insert_char(port, 0, 0, c, TTY_NORMAL);/*the flag is always TTY_NORMAL as we don’t implement any error checking*/

/*statistics*/

port->icount.rx++;

}

/*when done with insertion, send data to tty layer*/

tty_flip_buffer_push(&port->state->port);

}

Close_fct:

Lastly, we implement the close function to properly free the used resources: free IRQ + free GPIOs + kill any scheduled tasklet.

int uart_exit(void)

{

/*free IRQ*/

free_irq(gpio_to_irq(gpio_rx), NULL);

/*free gpio*/

gpio_free(gpio_tx);

gpio_free(gpio_rx);

/*kill rx tasklet*/

tasklet_kill(&rx_tasklet);

return 0;

}

At the end of the implementation we can test our code by registering it directly as a simple module (not tty) and verify the correctness of the output using a logic analyzer or simply connecting the GPIO pins 17 & 27 to the ports of a usb/serial adapter. Feel free to test this part yourself.

For me, I think we are done with this first part, long part, I will implement the top half of the driver in the part2 of this write-up. Also, for the testing part, we will see a real test of the driver in a Serial Line Internet Protocol (SLIP), all of that until the driver is complete.

See you in the next part.

A.L

References

Raspberry Pi uarts : https://www.raspberrypi.org/documentation/configuration/uart.md

Timing Errors in Serial Communication: http://www.robotroom.com/Asynchronous-SerialCommunication-2.html

Linux serial driver : https://bootlin.com/doc/legacy/serial-drivers/linux-serial-drivers.pdf

Chapter 18. TTY Drivers : https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/linux-devicedrivers/0596005903/ch18.html