Linux kernel module : Building a soft UART for the Raspberry Pi - part2

In the first part of this writeup we introduced our project of building a software UART Linux driver and we showed the implementation of the UART protocol, the low-level part of the driver. In this part, we will continue on implementing the driver’s top layer, and after it’s complete, we will begin the testing part by using our softUART as a Serial Line Internet Protocol (SLIP) port.

Top Half

In this layer we will focus on implementing our serial driver. As mentioned in the previous part, we will build the driver upon the serial core interface.

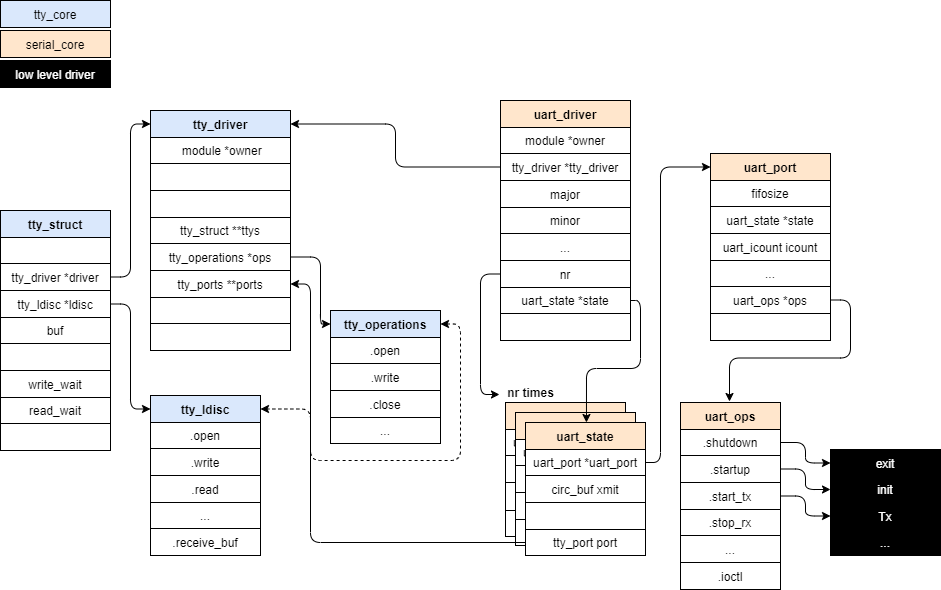

If you recall, from the diagram above, we have three main structures to define for the driver:

- The structure representing the actual driver:

struct uart_driver- Registered using the function

uart_register_driver(&uart_driver)

- Registered using the function

- The structure representing the port included in the driver:

struct uart_port- One instance for each port in the driver (at least one port must be defined. It’s possible to have many ports in a driver:

nrports exactly) - Each port needs to added to the driver using the function

uart_add_one_port(&uart_driver, &uart_port)

- One instance for each port in the driver (at least one port must be defined. It’s possible to have many ports in a driver:

- The structure containing the pointers to the port operations:

struct uart_ops

uart_state and tty_driver structures are automatically initialized when the driver is registered in the kernel, and they must not be defined.

In a new file module.c we start the definition of the top half of our driver:

-

uart_driverstructure:We start by defining our

uart_driverstructure in which we give the driver a name, assign a major and a minor number to it, along with the number of ports the driver contains: only one port in our case.static struct uart_driver softUart_driver = { .owner = THIS_MODULE, .driver_name = "ttySOFT", .dev_name = "ttySOFT", /*the name that will appear under /dev */ .major = 240, .minor = 0, .nr = 1, /*number of ports in this driver*/ }; -

uart_portstructure:In this structure we initialize the

FIFOmemory size (set to 1024 bytes), we set the pointer to ouruart_opsstructure and we specify the driver type (serial driver):struct uart_port softUart_port = { .fifosize = FIFO_SIZE, /*tx & rx buffer size*/ .ops = &softUart_ops, .type = TTY_DRIVER_TYPE_SERIAL, /*driver of type serial*/ }; -

uart_opsstructure:This structure defines the operations of the port (start Tx, stop …). It includes the support for a set of functions that allows the control of the hardware serial port functionalities. In our case, as we are not interested in emulating all the hardware port characteristics, we only need to implement the minimal set of functions for a normal working of the port. Below is the set of functions defined in the

uart_opsstructure:static struct uart_ops softUart_ops = { .tx_empty = softUart_tx_empty, //return TIOCSER_TEMT if tx_buffer is empty, otherwise return 0 .get_mctrl = softUart_get_mctrl, //get modem ctrl : return CAR|CTS|DSR .start_tx = softUart_start_tx, //called by write() : start transmitting chars .startup = softUart_startup, //called by open(): initialize any low level driver state .shutdown = softUart_shutdown, //called by close() : Disable the port, and free any resources .set_termios = softUart_set_termios, //change the port parameters : only the baudrate change is permitted in our implementation .ioctl = softUart_ioctl, //Perform any port specific IOCTLs : We implement TCSETS command only. }; -

Define port operations:

After the definition of the three structures, lets now start the definition of the operations initialized in the

uart_opsstructure:- The

softUart_tx_empty()function verifies if the transmission buffer of the driver is empty. This function is called by the top layer (after each transmission) when it doesn’t receive a wakeup call from the low-level layer. If this function returns 0 (buffer not empty), a delay of 30 seconds is triggered automatically by the top layer. Therefore, to avoid this delay, we will block our function so it doesn’t return until the buffer is empty:

static unsigned int softUart_tx_empty(struct uart_port *port) { printk("...........tx_empty ! \n"); while(!isBufferEmpty(&tx_buffer)); // wait until buffer is empty return TIOCSER_TEMT; }- The

softUart_get_mctrl()function is called when the port is initialized. This function returns the state of the different physical signals of the serial port. In our case, we don’t implement any control signal, however, in this function, we need to return that these three signals are permanently enabled: theCARsignal (DCD: Carrier Detect),CTS(Clear To Send) and theDSR(Data Set Ready)

static unsigned int softUart_get_mctrl(struct uart_port *port) { printk("...........get_mctrl ! \n"); return TIOCM_CAR | TIOCM_CTS | TIOCM_DSR; }- The

softUart_start_tx()function is called when thewrite()operation is called on the port. As its name implies, its role is to begin data transmission. The data to-send is stored in a circular buffer calledxmitand accessible via theuart_portpointer:port->state->xmit

In this function, we start firstly by copying the to-send data from the top layer circular buffer

xmitto theTx_bufferof our low-level driver (we used for that thepush_string()function defined previously incircular_buffer.h).After copying, we update the

xmitbuffer pointers: tail and head, and we call our low-level functionuart_handle_tx()to send the data via theGPIOport:static void softUart_start_tx(struct uart_port *port) { printk("...........start_tx ! \n"); /*copy data from xmit to tx_buffer*/ push_string(&tx_buffer, (unsigned char *)(port->state->xmit.buf + port->state->xmit.tail), uart_circ_chars_pending(&port->state->xmit)); /*update xmit tail*/ port->state->xmit.tail = port->state->xmit.head; /*start tx*/ uart_handle_tx(port); }- The

softUart_startup()function is called when theopen()operation is called on the driver. Its role is to initialize the low-level hardware. In this function we simply call theuart_init()function:

static int softUart_startup(struct uart_port *port) { printk("...........startup! \n"); uart_init(GPIO_TX,GPIO_RX, port); }- The

softUart_shutdown()function is called when theclose()operation is called on the driver. Its role is to close the port and free all used resources:

static void softUart_shutdown(struct uart_port *port) { printk("...........shutdown! \n"); uart_exit(); }- The

softUart_set_termios()function is used by the user to set/get the configuration of the serial port: parity, data word size… In our case, as it’s a limited implementation, we will only allow baudrate changes (also, as it will be discussed later, our implementation imposes a max and min for the baudrate). This function is called when theset_termios()function from the librarytermios.his called:

static void softUart_set_termios(struct uart_port *port, struct ktermios *new, struct ktermios *old) { printk("...........set_termios ! \n"); unsigned int baud; baud = tty_termios_baud_rate(new);/*convert the desired baudrate from ktermios arg*/ if (baud >= MIN_BAUDRATE && baud <= MAX_BAUDRATE) uart_set_baudrate(baud); else printk(KERN_WARNING "default Baudrate of 9600 is used ! \n"); if((new->c_cflag & CS8) != CS8) printk(KERN_WARNING "Only 8bit data size is available ! \n"); if((new->c_cflag & PARENB) || (new->c_cflag & PARODD)) printk(KERN_WARNING "No parity bit is available ! \n"); }- The

softUart_ioctl()function is pretty the same as the previous one, we define it only for compatibility reasons. This function is called when theioctl()operation is called on the driver, and it’s used to set/get the configuration of the serial port. We will add the support for only oneioctlcommand, which isTCSETS, that is used to set the serial port settings. If this command is called, we change only the baudrate and leave everything as it is:

static int softUart_ioctl(struct uart_port *port, unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg) { printk("...........ioctl cmd : %x ! \n",cmd); if (cmd == TCSETS) { struct termios *tty = (struct termios *) arg; if((tty->c_cflag & B19200) == B19200) uart_set_baudrate(19200); else if((tty->c_cflag & B9600) == B9600) uart_set_baudrate(9600); else if((tty->c_cflag & B4800) == B4800) uart_set_baudrate(4800); else if((tty->c_cflag & B1200) == B1200) uart_set_baudrate(1200); else { printk("default Baudrate of 9600 is used ! \n"); } return 0; } return -ENOIOCTLCMD; /*mandatory return if cmd not supported*/ } - The

note: To ease the driver debugging and to better understand when each operation is called, I added for each operation a

printk(“…….function name !”).

- Module

initand moduleexit:

After defining all the necessary operations, now we need to define the module_init and module_exit functions. These two functions are the homologue of the main() function in a regular program and they are as mandatory as the main() function is. The init function is the function that is called when the driver is loaded into the Linux kernel, and the exit one is called when the driver is unloaded

- In

module_initfunction we register our serial driver along with its port usinguart_register_driver()anduart_add_one_port()functions:

static int __init mymodule_init(void)

{

int ret;

ret = uart_register_driver(&softUart_driver);

if (ret) {

printk(KERN_ERR "softUart: could not register driver: %d\n", ret);

return ret;

}

ret = uart_add_one_port(&softUart_driver, &softUart_port);

if (ret) {

printk(KERN_ERR "softUart: could not add port: %d\n", ret);

uart_unregister_driver(&softUart_driver);

return ret;

}

printk(KERN_INFO "Module initilized ! \n");

return 0;

}

- In

module_exitwe unregister the driver and its port in the reverse order of registering: first unregistering the port and then the driver.

static void __exit mymodule_exit(void)

{

uart_remove_one_port(&softUart_driver, &softUart_port);

uart_unregister_driver(&softUart_driver);

printk(KERN_INFO "Bye. \n");

}

Compilation

To compile our Linux module, we need to have on our system the Linux headers of the kernel on which the module will run. These headers provide the various function and structure definitions required when compiling code that interfaces with the kernel. If you are using a RPi executing the latest Raspbian image with internet access for development, the command below is sufficient to get the headers for your Linux kernel version:

$ sudo apt-get install raspberrypi-kernel-headers

In my case, as my RPi doesn’t execute the latest Raspbian image, the command above gave me a much recent kernel headers version which is not compatible with my kernel version, so i had to install it manually. (if you want to find out your image kernel version, execute the command: $ uname -a)

The trick I used to get the proper Linux kernel headers version, is by searching in the Debian archive repository http://archive.raspberrypi.org/debian/pool/main/r/raspberrypi-firmware/ for all the previous versions of the raspberrypi-kernel-headers package and download the one corresponding to my kernel version. Remembering the time I downloaded the Raspbian image, made it really easy to guess which package is the one, as each package has a publication date. Packages in the archive are disposed as deb files and can be installed using the command below:

$ sudo dpkg -i raspberrypi-kernel-headers_<pack-version>_armhf.deb

Note : if you can’t remember the date your image came out , you can install the packages one by one until you find the proper version. The package manager will automatically downgrade when you install older versions (the installed headers can be found under /usr/src/ folder).

After we got the Linux headers, we can now compile our module using the makefile below:

obj-m += Mymod.o

Mymod-objs := circular_buffer.o soft_uart.o module.o

RELEASE = $(shell uname -r)

LINUX_HEADERS = /usr/src/linux-headers-$(RELEASE)

all:

$(MAKE) -C $(LINUX_HEADERS) M=$(PWD) modules

clean:

$(MAKE) -C $(LINUX_HEADERS) M=$(PWD) clean

where the variable LINUX_HEADERS points to the path of the Linux headers.

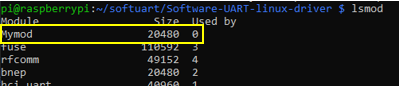

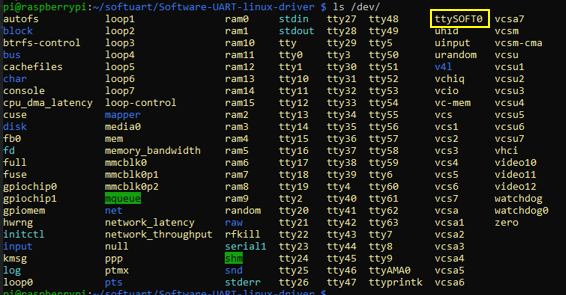

After successful compilation we obtain a file with the extension .ko (kernel object) which corresponds to our module object. To load the module into the kernel we use the command below:

$ insmod Mymod.ko

If we check now under the /dev path we can find that our serial port appears as a TTY device named ttySOFT0 indicating a successful registration of our driver under the TTY subsystem of the kernel.

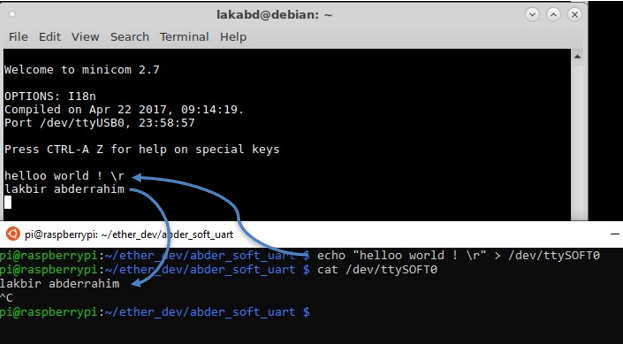

The figure below shows the first test of our driver. I used a serial/usb adapter to connect to the Raspberry ports 17 and 27, via the minicom console:

As we can see, our SoftUART driver is working properly in both Tx and Rx modes. As of the baudrate, the max allowed value for proper functioning of the driver was found to be 19200, beyond this baudrate, all exchanged data are corrupted.

This limitation is well expected: a rise in the baudrate will tighten the timing constraints on our system and will end up by exceeding its capabilities as our implementation is prone to a lot of preemption. However, if we limit our baudrate below the max value, no difference can be noticed compared to a hardware peripheral.

Serial Line Internet Protocol

Coming soon…

A.L

References

Low Level Serial API : https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/serial/driver

Chapter 18. TTY Drivers : https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/linux-devicedrivers/0596005903/ch18.html

Linux TTY driver–Uart_driver bottom layer : https://blog.csdn.net/sharecode/article/details/9196591

Linux uart underlying device driver detailed : https://blog.csdn.net/weixin_38696651/article/details/89431600

A preliminary study of tty-analysis of uart driver framework : https://blog.csdn.net/lizuobin2/article/details/51773305/